Older Callet Ideas

The ideas shared on this page are based on Jerome Callet’s older teaching. Understanding these ideas is not essential to learning TCE, but they are very helpful for understanding correct embouchure function in general. As with everything on this website, you’re not going to fully grasp a technique from reading one person’s 5-page explanation. TCE is something that you learn through its practice and this information is just here to as a source of knowledge to those who seek it.

What The Lips Need To Do

When it comes down to it, this is what understanding brass player’s embouchures is all about. Although the tongue plays an active role developing the TCE, the real way that this playing system can be compared, contrasted and understood alongside other approaches is through analysis of the lips. For the most part this page is based upon the material from Callet’s 1987 book and VHS Superchops and for many players it is all of the information they need to kick-start a massive positive change in their playing abilities. Why? A major function of the brass player’s embouchure is to resist the flow of air. It is the valve that controls air pressure. Inter-oral pressure is what controls pitch, timbre and dynamics. Quality brass playing is the controlled release of pressurised air. To many these statements may seem backwards and unusual, but missing this fundamental lesson is the reason that many brass players fail. A lot of people are teaching players to use more air, and to expel it as quickly as they can. That approach will never result in a strong player or a controlled sound. This concept is visited again on the Correct Use Of Air page.

Flat chin?

In order for a player use their full body strength in playing they need to have some resistance to push against. Problems arise, however, when we take a look at the traditional approach to setting the lips prior to and during the production of sound. The most common embouchure taught in the UK is often referred to as the Farkas type as a nod to French Horn player Philip Farkas, who famously wrote his observations of himself and other accomplished players who all played with a flattened chin. The flat chin is generally a result of tightening the corners of the mouth and stretching the bottom lip prior to placement of the mouthpiece. In the past it has been recognised by teachers, including Donald Reinhardt, that a loose bottom lip is the cause of many brass players’ embouchure issues. Unfortunately their solution to this issue was to pin the lip down against the teeth by tightening the corners of the mouth. This action restricts movement, pulls the aperture between the lips apart and is generally tiring to maintain. Tightening the corners and flattening the chin causes more problems than it solves.

“Tighten the lips”

Training band directors and primary school peripatetic teachers across the world use these words on a daily basis to the detriment of all aspiring brass players. First of all, it actually doesn’t make sense. Tighten them how? I’ve quizzed many a young learner about what they’ve understood when given this instruction and overwhelmingly the answer is that they didn’t understand. The rest of them did understand and do the wrong thing, as instructed. What we need to be saying is “move the lips” and then follow that up with a diagram of which direction to move them in. instinctively players will stretch the lips away from the mouthpiece, often thinking of the top lip as behaving in the same way as a vibrating string. This idea is incorrect. As the lips stretch laterally the lip tissue becomes thinner and the lip aperture becomes warped. This makes the lip weaker and less able to vibrate and can be heard as the tone losing core and intonation becoming distorted as one ascends a scale. It also makes the embouchure much less capable of controlling the release of air and the most normal compensation for that is the addition of mouthpiece pressure.

Creating The Correct Resistance

In order to best control the release of air through the lips, the point of maximum resistance needs to be as close to the point that the air is released as possible. Creating resistance anywhere else, for example behind the teeth with the tongue or in the throat, is akin to putting a kink in a hosepipe and the result is not that which is wanted. Some pedagogues describe the air flowing over the tongue as it travels through the mouth, but these ideas are old-fashioned and incorrect. The reason for that being that we are dealing with a closed system containing a compressible fluid, not a liquid moving from one place to another. The distinction here is very important. As stated above, the pressure inside the mouth is what determines pitch, dynamic and timbre. As pressurised air escapes through the lips a standing wave is excited within the instrument and the lips vibrate in sympathy with that wave. It is the air inside the instrument that makes the sound, not the flow of air through the instrument. You can read about that more on the Physics Of Brass Playing page.

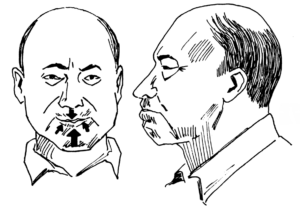

The way to correctly move the lips to resist the air is best shown with the following picture:

Learning to make these movements correctly can be hard work, especially if learning to do so by conscious effort. Instead it is mostly influenced by the initial setting of the mouthpiece onto relaxed lips, the practice of Einsetzen/Ansetzen exercises and anchoring the tongue on the bottom lip. A lot of the difficulty that players experience is the effort of fighting old habits that pull the lips away from the centre.

In the 1980s this movement of the lips was the primary focus of Jerome Callet’s teaching and he would advise people that the bottom lip should move upwards over the top teeth as you ascend in pitch. With the addition of the anchored tongue on the bottom lip this is no longer necessary but the movement is the same. The mouth corners need to remain relaxed and the bottom lip moving upwards against the tongue assists in resisting the air. For those who find it hard to anchor the tongue at first, establishing this movement will help to solve that problem as stretching the lips makes the forward tongue position much more difficult.